It is hard to believe it has been 20 years since the first batch of Real Pickles was created! This year, through the rainy days of cucumber slicing, now into the season of cabbage coring, shredding and mixing, and looking forward to more beets and carrots in the colder months…. we’re reflecting on the simplicity of that first year and how far we’ve come as a social enterprise. The summer of 2001, Real Pickles was just one young person slicing cukes in the early hours, fermenting in 5-gallon buckets, and driving around the valley to sell a few jars out the back of an old Saab to a handful of willing shops. It was a short-lived season too – the 1,000 jars produced were sold out by Thanksgiving!

However, the simplicity is only in hindsight. Starting a business is NOT a simple task, as many of you know. Real Pickles’ success and stamina have much to do with the fabric of a supportive community, and the many elements that came together to help a burgeoning business survive… and eventually thrive.

We write today to say, “THANK YOU to our community for supporting Real Pickles for the past 20 years!” We mention here just a few of the organizations that made our path viable, though there are countless individuals and groups who have supported us over the years. We can only trust that offering a colorful and nourishing line of ferments – combined with an ongoing commitment to making positive social change – is an acceptable return.

Local Farms, Local Heroes

When the idea of Real Pickles was first conceived around a kitchen table in Somerville, MA, founder Dan was working at Iggy’s Breads and I was finishing up my last college semester, ready to embark on a career in geology. Dan had taken a workshop at the Northeast Organic Farming Association (NOFA) summer conference, a convergence of practitioners and students engaged in organic farming and homesteading. NOFA has built a culture of knowledge sharing, skill-building, and advocacy; it was a fitting atmosphere for a future entrepreneur to find inspiration in the near-forgotten art of lacto-fermentation. As a couple, we were wondering, “where to next?” To start a fermentation business, we knew it had to be a place with strong organic agriculture and appreciation for local food and economies. Western Massachusetts fit the bill better than we could have imagined.

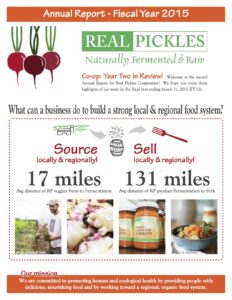

Not only does this area have some of the best farmland in the country, it is a training ground for skilled organic farmers. The growers from whom we source our vegetables bring deep expertise to cultivating the highest-quality vegetables with top priorities of improving the health of the soil and surrounding ecosystems and supporting the workers that grow our food. That first year, we bought cucumbers from Chamutka Farm and Red Fire Farm and have continued to buy their vegetables every year since, while expanding our network to include a half dozen other local farms. These partnerships are integral to our business, especially given our commitment to 100% regionally-grown and organic vegetables.

The Connecticut River Valley is also a hub for community appreciation of local and organic food. Full of food co-ops, farm stands, and independent markets, there were many shops that were ready to take a chance on a tiny food business producing an unusual but nourishing product. The first day of deliveries included stops at Leverett Food Co-op, Green Fields Market, Foster’s Supermarket, and Brookfield Farm. All are still important partners for us, and we deeply appreciate their early and continued support. In a valley with sweeping farmland views, this community is invested in the success of food grown and produced here. Much of that appreciation stems from the important work of Community Involved in Sustaining Agriculture (CISA). Shortly before our arrival, CISA had launched the Be a Local Hero, Buy Locally Grown marketing and education campaign that grew our community’s appreciation and commitment to local food. Local Heroes are the farmers, food producers, and consumers who choose locally-grown products and support our local agricultural economy. CISA has continued to be one of our most important community partners in spreading awareness of the benefits of a vibrant local farming and food culture.

That first summer of pickle production we relied on generous offers from local business people, such as an Amherst restauranteur who loaned her commercial kitchen in the early morning hours for our production and a Greenfield ice cream maker who lent refrigerator space. We greatly appreciated these critical opportunities and soon found that we needed a new option to scale up production. Luckily, another crucial partner in the Real Pickles story, the Franklin County Community Development Corporation (FCCDC), was about to unveil their brand new Western MA Food Processing Center in Greenfield. For the next seven years, we made excellent use of this incubator kitchen, plus the lending and technical assistance provided by the FCCDC to grow our product line, hone our business skills, and develop relationships with other food and small business owners.

Thinking back, it is hard to imagine that Real Pickles could have lasted long without these initial community partnerships.

Community with Big Hearts and Know-How

Over the next few years, I jumped in and together we grew the business at the Food Processing Center with help from a network of informal advisors and advocates. These included other small business owners who had experience with manufacturing, accounting, sales, marketing, and growing pains. We attended food and farming events to introduce our products and talk to people. In our social time, we went to contra dances where the community readily embraced Real Pickles and spread the word across New England. The late caller-fiddler David Kaynor would frequently hold up our bartered jar to a crowd of 200+ dancers and wax eloquently about the flavor and benefits of fermented pickles. We feel so privileged for this community of enthusiasts and spokespeople that helped to garner support for our products across the region.

And then there are all of the eaters of fermented foods. Thankfully, this area is full of people with adventurous palettes! We had the added challenge of trying to build consumer awareness of fermented foods, which 20 years ago was not the trending natural products category that it is today. There were only a handful of producers across the country making products like ours, and in many stores ours was the only line. An effervescent thank you to all our early customers willing to give fermented vegetables a try!

As we began to outgrow the incubator kitchen, it took a broad array of community support to help us make the leap to our own facility. In 2009 we purchased a century-old industrial building in Greenfield and transformed it into a solar-powered, energy-efficient, organic pickling facility. It was a challenging transition to say the least, one that we managed to pull off only because we had community partners who believed in us. A crucial element was the financing, of course. In spite of our already high debt load and a new global recession, our outstanding local bank and two mission-driven nonprofit lenders (Equity Trust, and FCCDC) came through for us just as we began to wonder if it was time to give up on Real Pickles. We are deeply thankful for all of the individuals and organizations who helped Real Pickles make it past that critical juncture.

Multiple bottom lines… into the future

Since that time, Real Pickles has grown and developed into an organization that relies on many hands to operate. Our growing staff over the years have been an essential component of the business, and we are forever grateful to all those who have contributed by packing sauerkraut, chopping carrots, and building a strong culture. In 2013, along with three other staff (Brendan, Kristin, and Annie), we made the decision to convert Real Pickles to a worker-owned co-operative. This transition offered strong mission protection, opportunity for staff to benefit from owning their workplace, and assurance that Real Pickles will remain a community-oriented business far into the future.

To make this transition happen, we relied on the support of 77 community investors to join us in this endeavor. Folks were excited about supporting a business committed to healthy food, regional agriculture, and workplace democracy. By becoming a worker co-operative, we are building ownership in our community and creating good jobs in an inclusive work environment. We’re proud to be in a place where so many people value these things and are willing to invest in building a better food system.

As we move forward into the next 20 years, we do so knowing we are a community business. Our community partners – farmers, customers, investors, vendors, lenders, and many more – continue to play an essential role in our success. We in turn take responsibility for operating a truly mission-driven business that tracks multiple bottom lines – financial, social, and environmental. One important piece of this is acknowledging the role of social privilege in our founding success and a commitment to applying our resources toward building a more equitable society for the future. Building on the strength and values of our community, we will continue to make the world a better place and we commit to this for the long term.

THANK YOU to everyone who has contributed to our story over the past 20 years — we’re lifting a glass of Organic Beet Kvass in your honor!

How many truckloads of regionally-produced food do you deliver to New York City & Boston each year?

How many truckloads of regionally-produced food do you deliver to New York City & Boston each year? With all the farms and food producers in Vermont and the Pioneer Valley, how do you choose your offerings?

With all the farms and food producers in Vermont and the Pioneer Valley, how do you choose your offerings?

These are essential questions for anyone who wants a better food system – one that is ecologically sound and socially just. After all, a big impetus for the rapidly growing movement to transform the food system is the modern-day reality that places like New England – quite capable of raising such crops as apples or tomatoes – will instead import them from thousands of miles away and burn up large quantities of climate-changing fossil fuels in the process.

These are essential questions for anyone who wants a better food system – one that is ecologically sound and socially just. After all, a big impetus for the rapidly growing movement to transform the food system is the modern-day reality that places like New England – quite capable of raising such crops as apples or tomatoes – will instead import them from thousands of miles away and burn up large quantities of climate-changing fossil fuels in the process.

The change in Real Pickles’ ownership provides a number of collateral

The change in Real Pickles’ ownership provides a number of collateral