The extraordinary political events taking place in our country are affecting us deeply here at Real Pickles Co-operative, as they are for so many others. They highlight how far we have to go to build the just, democratic, and sustainable society we wish to see. We are reminded why all of us here take Real Pickles’ social mission so seriously, and why we must continue to work as hard as we can in pursuit of it. It is also now as clear as ever that we cannot do this work alone.

One essential lesson of the 2016 presidential election – among many others – seems to be that our economic system is truly not working for many millions of Americans, and that this fact cannot be ignored. The Dow Jones may be up, the economy may be growing, corporate profits and the 1% may be doing great. But many are being left behind. Real change is needed, and the big question is what kind of change will we work toward?

At Real Pickles, we are committed to creating positive social change based on an inclusive vision that prioritizes equality, justice, health, democracy, and sustainability. We are seeking to build a system that offers real opportunity to all people to live healthy and fulfilling lives. This means moving away from corporate capitalism and toward an economy where small, community-oriented businesses are the norm. It means making hatred and discrimination things of the past. And – urgently – it means doing whatever we can to avoid disastrous climate change.

Thankfully, we are far from alone in these efforts. A strong example is the New Economy Coalition (of which we are a proud member), whose vision is “a new economy…that meets human needs, enhances the quality of life, and allows us to live in balance with nature…a future where capital (wealth and the means of creating it) is a tool of the people, not the other way around.” As a diverse array of 175 member organizations, each is pursuing these goals in its own ways, and also coming together wherever and however possible to build on each other’s efforts. So much essential work is happening within this network, and we are grateful for the opportunities we’ve had to collaborate with such members as Equity Trust, Co-op Power, Cooperative Fund of New England, Cutting Edge Capital, Tellus Institute, Slow Money, and Project Equity.

Our work of creating a more sustainable food system is supported by many thriving organizations. Community Involved in Sustaining Agriculture (CISA), for example, has been paving the way for countless food and farm businesses here in western Massachusetts to reach success as a result of their highly effective marketing of the “buy local” concept. The Northeast Sustainable Agriculture Working Group (NESAWG), a 12-state network of over 500 organizations, is leading the way in building a vibrant regional food system. The Northeast Organic Farming Association and Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association are each in their fifth decade as influential developers of the organic agriculture movement.

We are also encouraged to be seeing the rise of the co-operative movement which is building a valuable alternative to the traditional corporate model. Worker co-operatives are sprouting up here in western Massachusetts (and elsewhere), with the Valley Alliance of Worker Cooperatives providing a forum for area worker co-ops to collaborate as well as offering assistance to start-ups. Around the Northeast, we are seeing more and more consumer food co-ops both getting started and expanding, with support from the Neighboring Food Co-op Association – a regional network of food co-ops representing combined memberships of over 107,000 and annual revenue of $240 million.

While the primary focus of Real Pickles’ work is the Northeast U.S., we recognize the importance of maintaining a national and global perspective, as well. We admire and support the grassroots climate activism of 350.org, and have participated in climate marches in NYC and Washington DC. The National Co-op Business Association, a national trade group of co-ops, is doing important work developing and advancing co-operative enterprise both in the U.S. and internationally. The Cornucopia Institute is providing the public with essential reporting highlighting both the problems of industrial agriculture and beneficial practices of family-scale organic farmers. Over the past year, thousands have been camped out on the front lines protesting plans to build the Dakota Access Pipeline near the Standing Rock Sioux reservation (we recently made an exception to our Northeast-only distribution commitment to send a donation of fermented vegetables to the protesters).

We’re deeply fortunate to be working with so many effective partners who share our commitment to a just, democratic, and sustainable society. At the same time, we know that our approach to creating social change, as well as the scope of our own network, represents merely a narrow slice of what is happening and what must happen if we are to truly achieve our vision. In the months and years ahead, we commit to redoubling our efforts to create real and positive change by building on the work we’re already doing and by seeking out new connections and partnerships across our region, nationally and globally. We hope you will join us.

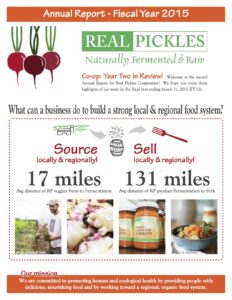

These are essential questions for anyone who wants a better food system – one that is ecologically sound and socially just. After all, a big impetus for the rapidly growing movement to transform the food system is the modern-day reality that places like New England – quite capable of raising such crops as apples or tomatoes – will instead import them from thousands of miles away and burn up large quantities of climate-changing fossil fuels in the process.

These are essential questions for anyone who wants a better food system – one that is ecologically sound and socially just. After all, a big impetus for the rapidly growing movement to transform the food system is the modern-day reality that places like New England – quite capable of raising such crops as apples or tomatoes – will instead import them from thousands of miles away and burn up large quantities of climate-changing fossil fuels in the process.